On Monday morning, Pyotr Pavlensky set fire to the door of Russia's most powerful and publicly symbolic security agency. On Tuesday evening, Marco Rubio made a polemical claim in two parts aimed at academics, first asserting that "Welders make more money than philosophers," before following up with "We need more welders and less[sic] philosophers." The first part is probably false, depending on who you count as a philosopher, and the second part is arguably true simply because there's something of a shortage of welders at the moment. But regardless of whether you credit the content of his assertions, you probably wouldn't suppose that they have much to do with Pavlensky's brave and spectacular act of protest. I am going to argue that they do, that the welder's torch burns at one end of a vital spectrum of human activity and Pavlensky's gasoline burns at the other. Because I am, after all, a philosopher, there will be a good deal of exposition. But I hope that what follows will be a demonstration as well, because a great deal of it will concern the practice of philosophy itself.

Much of the immediate reaction to Rubio's salvo, particularly on the part of philosophers, was to decry it as inaccurate. I respect this concern for accuracy, but in this case it doesn't interest me terribly. I am more intrigued by just what it is that Rubio was getting at, what sort of a point he meant to make. Here are two reasonable ways to parse his claim:

- "Welders make more money than philosophers, and you should support me because I will get people training as welders, and then they will make more money than if they had gone to college and become philosophers as others would have them do."

- "Welders make more money than philosophers, and this is a sign that they contribute more to society. I will grow the economy by providing training for more welders, who will thus be more productive than if they were philosophers."

The first version is more immediately susceptible to fact-checking, and as it turns out it doesn't hold up. But in light of the later part of his remarks, I would suggest that the second interpretation is closer to what Rubio intended. Like most of the Republican candidates, he presents himself as a capitalist both as a matter of values and as a matter of economic theory. He isn't trying to rally people who want to make more money by promising them welding jobs, that would be a bit silly. He's trying to rally people who believe that having more welders around will make us all more prosperous, because the goods they produce will both benefit us and translate into money that the prosperous welders will spend at other businesses. And obviously they are intended as a sort of synecdoche of "vocational" professions more broadly.

Right here, though, I've already shown one of the weaknesses of this kind of claim. In order to tease out the most plausible version of it, I've employed the basic tools of philosophy. I began by wondering which interpretation was most internally consistent, given his other remarks and ideological commitments. I've been charitable, which is a more important part of philosophy than you might think, and assumed that the more coherent and defensible claim was the one he meant to make. Now let's presume, a little simplistically but in the spirit of the discussion, that we do need to make a choice about whether to invest in welding or philosophy. The skills we need to make the right choice, the wisest investment, are closer to the skills of the philosopher than the welder. This is not because one skill set is in some absolute sense more valuable than the other, but because training in philosophy is simply more appropriate to this particular task. Such training includes not only a lot of careful analysis of how to identify relevant considerations and draw careful conclusions from them, but also a lot of reading how others have gone about it so that you don't have to start from scratch. Philosophy is also very good for inoculating you against bullshit. It would probably be helpful for promoting a shrewd electorate, at least, if everyone got a little exposure to philosophy.

Going back a step, let's assume that (2) is roughly the proposition Marco Rubio meant to advance. It's easy to see why it struck such a nerve, not only with my immediate colleagues, but with many producers of knowledge and culture. It echoes a sentiment that we fear and resent, as we should, a terrible latter-day Frankenstein's monster stitched together out of the corpses of moldering values: the masochistic work ethic and prudish revulsion toward art of the Protestant, the moralized and superstitious fear of pagan knowledge of the Catholic, the lazy and arrogant materialism and self-absorption of the scientistic atheist. To be sure, none of these are necessary consequences of any particular religious or irreligious commitments. They are usually fallen, listless versions of how such views appear in their living forms. But in political discourse it has become common to see them shambling about, awkwardly assembled and tragically re-animated.

Why does the dull gaze of this monster tend to fall on the "Arts & Humanities"? There are probably a lot of reasons, but many of them are best understood by making a distinction between first-order and higher-order economic activity. First-order economic activity is most exemplified by direct participation in agriculture or industry, although there are many other forms of it as well. Generally speaking, first-order activities result in the production of commodities (things that can be traded and consumed) or the provision of services. Second-order economic activity is in some sense activity about first-order activity: organizing, critiquing, representing, and so forth. The modern period, which arrived very early for philosophy and shortly after came to dominate art and literature as well, is in part about about a rise in the prevalence and prominence of second-order activities, in the economic sphere as well as more generally. Philosophy has now ventured into third- and even forth-order territory, as suggested by the name of this blog, and inasmuch as other pursuits partake of postmodernism, they have as well. But the distinction between first- and higher-order is the most important; details about the various higher orders and the forms in which they appear needn't trouble us here.

This distinction will certainly not always be entirely crisp. Many activities cross multiple orders or seem (in some cases intentionally) ambiguous. Moreover, a few remarks are called for about what this distinction does not involve:

- It is not in and of itself a ranking. I'll be critiquing the primacy of first-order pursuits, but that is not the same thing as assuming some kind of superiority of higher-order pursuits.

- It is not about the material and immaterial or tangible and intangible. Musical performance, for example, is most often first-order even if it includes second-order elements, because it is the direct provision of an immediate experience. Duchamp and Breton's readymades are by definition material but are entirely higher-order.

- It actually has very little to do with income. Most highly profitable professions are in fact based on second-order activities.

It is fairly easy, if a tad jejune, to defend first-order activity. This is particularly true in popular debates about economics. But what really appeals to politicians like Rubio is taking cheap shots at higher-order activities, mostly in the process of explaining which deadbeats they intend to strip of their ill-gotten gains. This is also easy, because understanding the value of higher-order activities is a higher-order activity, so if you can prejudice people against it, you can lock them very firmly into your point of view. Nor is this only a strategy favored by the political right. A certain sort of Marxist—not exactly the most intelligent or faithful to their tradition and their canon, but a certain sort—will try and cut the world up along similar lines. On the one hand, the intuitive elegance and manifest success of this strategy does seem worrisome for all of us scholars and artists and such, especially those who are not exactly highly compensated for their work under present conditions. On the other hand, it a has a sort of fatal flaw:

Humans are inherently second-order creatures.

Philosophy of mind begins as any branch of philosophy must, with at least a working picture of its subject matter, of what the mind is. What could there be beyond the physical state of the brain? The best prospective answers rely in some way on the contents of our experience, and an important aspect of our experience is called intentionality. Intentionality is intimately connected to higher-order thinking. We often use it to indicate what you "meant to do", but in philosophy it refers to what you simply "meant", what your mind was pointing toward, what you were thinking about. The word is often used even more precisely to denote our capacity to refer, represent, etc. Really, it is more than a capacity, it is an inescapable function. We can't help it. We experience this directedness constantly, and project it onto the world in the form of symbols that seem to relay our attention through cascades of meaning. It is a fundamental feature of consciousness, maybe the fundamental feature; philosophers of mind sometimes refer to it as "the mark of the mental". There are many common aspects of human experience with higher-order features, particularly in language, and the majority are probably dependent on intentionality somewhere down the line.

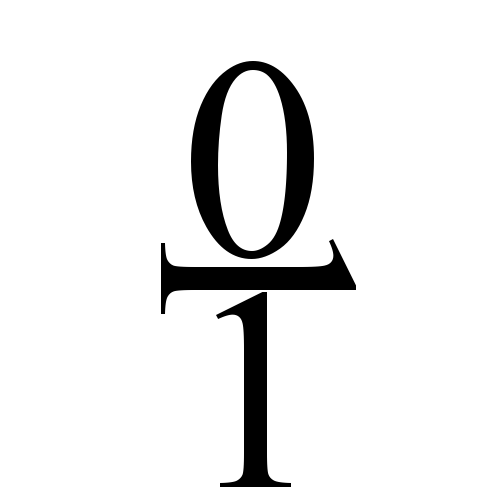

Which brings me back to Pavlensky. When you see this image, you can't help but wonder "Who is that? And where is that?" The first-order considerations, which from an economic perspective are simply a decline in the value of someone's front door, are obviously inadequate as a description of the situation. You immediately want to know more, and if "Lubyanka" and "FSB" don't mean anything to you, you'll ask more questions, and "KGB" will probably hit home. You'll have that moment where it all clicks, where you say "Oh..." and experience that sense of meaning. This is one reason why toddlers play the "Why?" game; in addition to a constant thirst for information, they are seeking a place for their intentionality to rest, something they can successfully mentally point to. Pavlensky is a master of forcing higher-order commentary into the consciousness of the public using incredibly visceral, first-order action.

A great many people in professions almost entirely concerned with second- and third-order economic functions seem to feel under siege lately, living on slim stipends or the last vestiges of their student loans and scanning the horizon for the grand armies of culture to arrive and save us. But they aren't coming. No such armies exist—there's only us. So perhaps we should take a page from Pavlensky's book and take the battle outside the gates of our lecture halls and studios. I am not suggesting that you should go set something on fire, though if that's the nature of your meta-... but I am suggesting that every intellectual needs to find some way to be a public intellectual, and all artists needs to understand themselves on some level as political artists. Whether or not the content of your work is part of a political conversation, you are still going to need to direct some of your skills toward shaping the public space. Many academics teach, obviously, and that is already an essentially social and political activity, whether they like it or not. Most of the ones I know pour everything they've got into it, and if their students didn't know what they were doing there on walking in, they sure as hell do by the time they leave. Many intellectuals and artists have activist commitments that aren't directly related to their work, and that's great too, because they can still bring a lot of commitment, skill, and innovation to social movements. A person's creative and scholarly work doesn't have to be her political work. There are a thousand ways to push the conversation, to remind people that caring about those wonderful first-order pursuits like welding and growing organics vegetables and fixing the roof is still human, second-order activity, because you are caring about it and that is your basic capacity and your right, as a human, to be all about something.

I should acknowledge that I'm casting my net rather presumptuously wide. Perhaps I should know better than to take philosophy as a synecdoche for a wildly diverse spectrum of creative and scholarly pursuits. So for my last few remarks, I'll restrain myself to the history of my own field. For us, for philosophers, this is an ancient hereditary battle. Misleading rhetoric is the predatory dark side of higher order thought, and in many ways, philosophy was born because people needed to figure out what made an argument more than sophistry. The inoculating ourselves against bullshit wasn't an afterthought, it was one of the first and most central goals of the discipline. And this was true not only in Athens, but in Chang'an, Kathmandu, Thebes, and probably in other areas for which we unfortunately have less of a written record. All around the world, this was the battle for which we armed ourselves. The techniques of philosophy are the grand panoply of the higher order, or more humbly, a tool-chest assembled for repairing and reinforcing the structures of public discourse. It's... kind of a fixer-upper.

So am I offended by Senator Rubio's remarks? Of course. But I am offended, not because they were directed against philosophers, but because they are examples of precisely the kind of things that frustrate philosophers. Half-sketched, sloppy arguments, stitched together from remnants of more vital theories, scaring people away from cultivating higher-order thinking so that they won't ask the important question: Living at the apex of human history in terms of technologies of first-order productivity, why can't we have plenty of welders and philosophers, and pay all of them well?

We'll begin to explore that question next week, when I'll be writing about the proper definition and general significance of economic rent.

Postscript: As I was putting the last touches on this post, tragic events unfolded in Paris that will quite rightly cast a shadow over most public conversations for some time to come. I don't know whether I will have anything direct to say about them here, but I do believe that we can best honor the victims of these appalling and ruthless crimes by keeping our conversations as civil and kind as possible, and as pointed and honest as necessary. The world became another bit colder on Friday, and so all labors of warmth are more vital than ever.

Your witty and carefully considered argument touches me. And I appreciate your timely closing remarks. I’m going to recommend the blog to others.

Thank you so much!